Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer a futuristic concept in medicine; it has become a present-day partner in the global fight against cancer. AI and Cancer are key topic in recent time. In the complex and demanding field of oncology, AI is driving profound breakthroughs in how cancers are detected, diagnosed, and treated. By analyzing medical data at a scale and speed that surpasses human capability, these sophisticated algorithms are empowering clinicians to make faster, smarter, and increasingly personalized decisions.

This article explores how AI algorithms are transforming the landscape of early cancer detection. It delves into the critical need for this technology, the science that powers it, its real-world performance backed by data and case studies, and the significant challenges that must be navigated to realize its full, life-saving potential. From identifying subtle abnormalities on a scan that are invisible to the human eye to predicting a tumor’s behavior, AI is emerging as an indispensable ally, helping to shift the odds decisively in the patient’s favor.

The Race Against Time: Why Early Cancer Detection is a Matter of Life and Death

The single most critical factor in determining a patient’s chance of survival is the stage at which their cancer is diagnosed. Progress over the last four decades has transformed the prospects for people with cancer, with survival rates doubling in the UK since the 1970s, largely due to improvements in detection. Put simply, detecting cancer early is the most effective weapon in the oncological arsenal.

The statistical evidence is stark and unambiguous. For many common cancers, the gap in survival rates between an early-stage and a late-stage diagnosis is a chasm.

- For colorectal cancer, the five-year net survival rate for a patient diagnosed at Stage 1 is an encouraging 93.4%. If that same cancer is not diagnosed until Stage 4, the survival rate decline to just 10.7%, a significant difference of 82.7 percentage points.

- The story is similar for lung cancer, one of the deadliest malignancies. Patients diagnosed at Stage 1 have a 57% chance of surviving for five years or more. For those diagnosed at Stage 4, that figure is only 3%. Other data shows that one-year survival for Stage 1 lung cancer is 87.3%, but it drops to only 18.7% for Stage

Despite this clear imperative, a significant portion of cancers are still discovered too late. Globally, approximately 50% of cancers are already at an advanced stage when they are first diagnosed. In England, for example, only 54% of cancers were detected at the more treatable Stage 1 or Stage 2 in 2018.

| The Impact of Early Diagnosis: 5-Year Survival Rates (Stage 1 vs. Stage 4) | |||

| Cancer Type | 5-Year Survival (Stage 1) | 5-Year Survival (Stage 4) | Survival Gap (Percentage Points) |

| Colorectal Cancer | 93.4% | 10.7% | 82.7 |

| Lung Cancer | 57.0% | 3.0% | 54.0 |

| Prostate Cancer | ~100% | 47.7% | >52.0 |

| Kidney Cancer | 88.9% | (Not specified, but significantly lower) | – |

| Data sourced from UK National Health Service and Office for National Statistics reports. | |||

A deeper look at the data reveals a fundamental challenge that technology is uniquely positioned to address. The cancers with the largest survival gaps, such as lung and colorectal, are often those that are “relatively asymptomatic” in their early stages. A persistent cough or non-specific stomach pain can be easily dismissed by patients or attributed to other conditions, allowing the disease to progress silently.

This is not merely a failure of screening technology but a biological and behavioral hurdle. It points to the immense potential for AI to find signals of disease long before physical symptoms become obvious, perhaps by analyzing subtle patterns in a patient’s electronic health records or blood tests.

This urgency is now being reflected in national health policies. The UK government, for instance, has set an ambitious target to diagnose 75% of all cancers at Stage 1 or Stage 2 by 2028. Such a goal creates a powerful top-down demand for innovative technologies that can make this a reality. AI is no longer just a subject of academic research; it is becoming a critical tool for achieving national public health objectives, driving funding, and reshaping the infrastructure of cancer care.

A New Partner in the Clinic: AI’s Multifaceted Role in Oncology (AI and Cancer)

To meet this challenge, AI is being integrated into clinical workflows not as a replacement for human experts, but as a powerful assistive tool that augments their skills. The core function of these AI systems is to process immense volumes of complex medical data, from images to genetic sequences, and detect subtle patterns that are often imperceptible to the human brain. This partnership is reshaping diagnostics across several key domains:

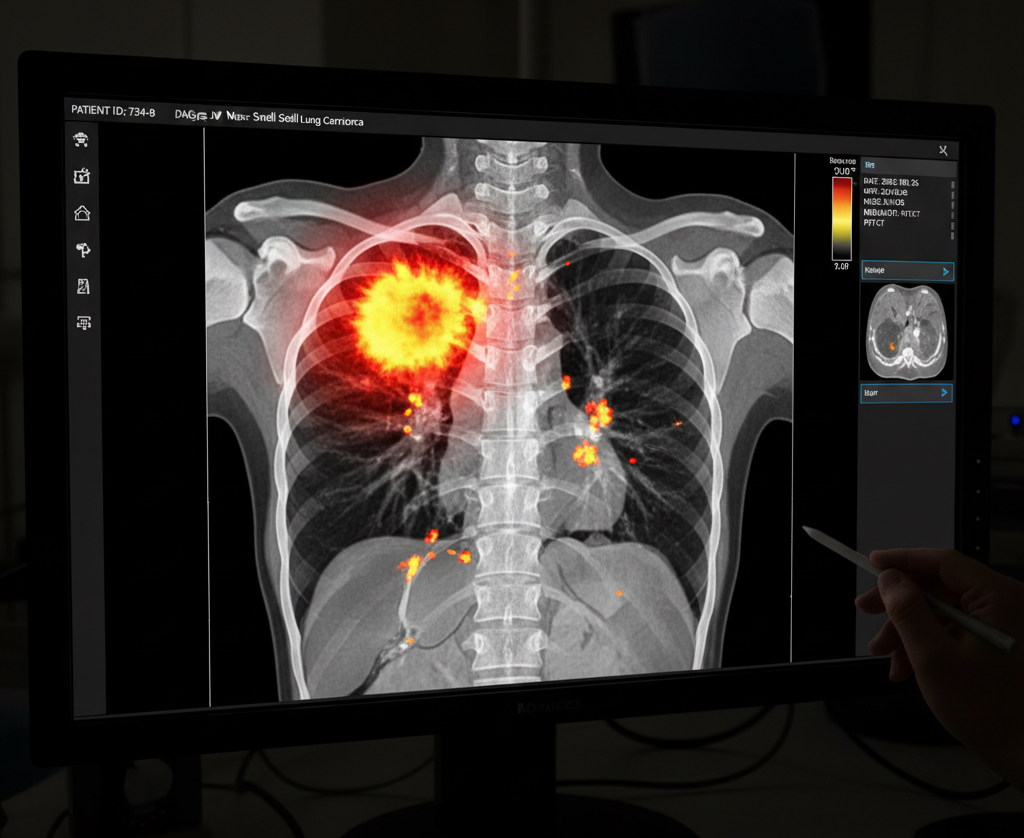

- Medical Imaging: This is where AI has made its most visible mark. Algorithms can analyze thousands of radiology images like mammograms, CT scans, and MRIs in seconds, flagging suspicious abnormalities that might be missed by the human eye.

- Digital Pathology: In pathology, AI models examine high-resolution digital images of biopsy samples. They can distinguish between benign and malignant cells, classify cancer subtypes, and even spot tiny clusters of metastatic cells that might otherwise be overlooked.

- Genomic Diagnostics: Modern cancer care relies on understanding a tumor’s genetic makeup. AI is invaluable for sifting through enormous genomic datasets to identify cancer-linked mutations, helping to guide personalized, targeted therapies.

- Risk Assessment: AI can mine millions of electronic health records (EHRs), using natural language processing to analyze doctors’ notes, lab results, and patient histories. This allows the system to identify and flag individuals at high risk for developing cancer, enabling proactive screening and earlier intervention.

The true value of this technology lies in the creation of a symbiotic relationship between clinician and algorithm. Human experts, such as radiologists, face enormous workloads and the challenge of “interobserver variability,” where different specialists may draw different conclusions from the same image. AI excels at the tireless, data-intensive task of initial analysis, providing a consistent and rapid first pass that reduces variability and flags areas of concern.

This save the clinician’s time and cognitive energy to focus on the most complex cases, apply their contextual understanding, and engage in the critical decision-making and patient communication that machines cannot replicate. The future of oncology is not a contest of man versus machine, but a powerful collaboration of man plus machine.

Under the Hood: A Simple Guide to the AI Engines Finding Cancer (AI and Cancer)

To appreciate how AI achieves these remarkable feats, it is essential to understand the core technologies driving this revolution. While the field is complex, the fundamental concepts can be understood through a few key ideas.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning

Machine Learning (ML) is a branch of AI where computers “learn” from data without being explicitly programmed for a specific task. In the context of cancer detection, instead of writing code that says “look for a circular shape with fuzzy borders,” developers feed an ML algorithm thousands of medical images that have already been labeled by experts as either “cancer” or “not cancer.” The algorithm analyzes these examples and learns the underlying patterns and features associated with each label. After this training process, it can then make predictions on new, unseen images.

Deep Learning (DL) is a more advanced and powerful subset of ML. It uses complex structures called “artificial neural networks,” which are inspired by the interconnected neurons in the human brain. These networks consist of many layers, and because they have multiple layers, they are considered “deep.” This depth allows the model to learn a hierarchy of features, starting with simple concepts and building up to more complex ones, which is particularly useful for analyzing intricate (complex) data like medical images.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): The Eyes of AI

For medical imaging, the undisputed star of deep learning is the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). CNNs are a specialized type of neural network designed specifically to process and analyze visual data. Their architecture is inspired by the animal visual cortex, where individual neurons respond only to stimuli in a specific part of the visual field. A CNN works in a similar, layered fashion:

- Convolutional Layers: The process begins with the convolutional layer. The CNN slides a small digital “filter” (also called a kernel) across every part of the input image. Each filter is designed to detect a very basic feature, like a horizontal edge, a vertical edge, a specific color, or a texture. As the filter moves, it creates a “feature map” that highlights where in the image that specific feature appears.

- Pooling Layers: After a convolutional layer, a pooling layer is often used. This layer effectively shrinks the feature map, keeping only the most essential information. For example, “max pooling” looks at a small window of the feature map and carries forward only the strongest signal. This makes the network more efficient and helps it focus on the most important patterns rather than getting lost in less important details.

- A Hierarchy of Features: The true power of a CNN comes from stacking many of these layers. The first layer might learn to detect simple edges. The next layer takes the maps of those edges as its input and learns to combine them into more complex shapes, like circles or angles, which might represent cell nuclei. A subsequent layer might learn to combine those shapes to recognize the structure of a tumor. This hierarchical process allows the CNN to build a sophisticated understanding of the image, from raw pixels to a final, high-level classification like “malignant”.

This approach represents a fundamental paradigm shift. In older computer-aided detection (CAD) systems, human engineers had to manually program the features the computer should look for. With CNNs, the network learns the most predictive features directly from the data itself.

This is why AI can sometimes identify patterns that are “invisible to the human eye”. It is not just mimicking how a radiologist thinks; it is discovering new, data-driven ways of seeing the image, which explains its potential to sometimes outperform human experts on specific, narrow tasks. Several well-known CNN architectures, such as VGG16, ResNet50, and AlexNet, are frequently cited in cancer detection research for their proven effectiveness.

AI in Action: Real-World Breakthroughs and Challenges

While the theory is promising, the true test of AI is its performance in the real world. A growing body of evidence from large-scale studies and clinical trials demonstrates both the immense potential and the significant challenges of deploying these algorithms in practice.

| AI Performance Snapshot: Real-World Case Studies | |||

| Cancer Type | AI Application/Study | Key Performance Metric(s) | Comparison to Standard Care |

| Breast Cancer | PRAIM Study | 17.6% higher cancer detection rate | Achieved with a similar recall rate, improving efficiency. |

| Lung Cancer | CT Scan Analysis (Systematic Review) | Sensitivity: +3% to +15% Specificity: -6% to -8% | Finds more cancers but at the cost of many more false positives. |

| Skin Cancer | DermaSensor Device | 96% sensitivity | Provides an objective, instant risk assessment to aid referral decisions. |

| Prostate Cancer | PI-CAI Study / Real-World Reviews | Research: AUC 0.91 vs. 0.86 Clinical: Performance drops up to 31% | Outperforms in controlled studies but struggles with the “translation gap.” |

| Performance metrics compiled from multiple sources.26 | |||

Breast Cancer: Improving the Gold Standard

Mammography is a cornerstone of public health, credited with significantly reducing breast cancer mortality. However, it is not perfect, suffering from both false positives (leading to unnecessary anxiety and biopsies) and false negatives (missed cancers).31 AI is proving to be a powerful tool to enhance this gold standard.

The PRAIM study, a massive, real-world implementation study in Germany involving over 460,000 women, provides compelling evidence. When AI was used to support the standard double reading of mammograms by two radiologists, the results were striking:

- The AI-supported group achieved a 17.6% higher breast cancer detection rate than the group with standard reading alone.

- Crucially, this improvement did not come at the cost of more false alarms. The “recall rate”—the percentage of women called back for further testing—was slightly lower in the AI group. This means the AI helped find more cancers more efficiently.

- The positive predictive value, or the likelihood that a recalled patient actually has cancer, was also higher with AI support (17.9% vs. 14.9%), indicating a more accurate screening process.

Other research supports these findings, with some studies showing AI can reduce false positives by 5.7% and false negatives by 9.4%, achieving higher sensitivity and specificity than the average radiologist on certain datasets.

Lung Cancer: The Sensitivity vs. Specificity Trade-off

For lung cancer, low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) is the most effective screening tool, but it is notorious for its high false-positive rate, as it often detects benign nodules. Here, AI presents a classic trade-off.

A comprehensive systematic review of AI’s performance in lung cancer screening found:

- The Upside (Higher Sensitivity): AI-assisted reading was significantly faster and improved sensitivity for detecting malignant nodules by +3% to +15% compared to unaided radiologists. This means fewer cancers are missed.

- The Downside (Lower Specificity): This gain in sensitivity came at the cost of a 6% to 8% decrease in specificity. In simple terms, the AI was more likely to flag benign nodules as suspicious.

- The Consequence: This trade-off has massive real-world implications. Researchers calculated that this drop in specificity could lead to an additional 60,000 to 80,000 people per million screened receiving unnecessary follow-up scans and surveillance. This creates not only a huge economic burden but also significant patient anxiety (“scanxiety”) and the risks associated with further invasive procedures. This highlights a critical dilemma: the benefit of finding more true cancers must be carefully weighed against the harm and cost of a dramatic increase in false positives. It is a complex ethical and economic question that the AI itself cannot answer.

Skin Cancer: An AI-Powered Handheld Device

AI’s impact is not limited to analyzing images in a hospital’s radiology department. The DermaSensor device is a prime example of AI being commercialized into a handheld tool for primary care physicians. Visual assessment of suspicious skin lesions is highly subjective, and this device aims to bring objectivity to the front lines of care.

- Technology: The FDA-cleared device uses a technique called Elastic Scattering Spectroscopy, which involves shining quick bursts of light onto a lesion and analyzing how it scatters. This data is fed into an AI algorithm trained on thousands of diagnosed lesions.

- Performance: The device demonstrates a 96% sensitivity for detecting the three most common types of skin cancer: melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma.

- Clinical Use: Within seconds, it provides a clear result: “Investigate Further” or “Monitor.” This empowers primary care physicians, who may not have specialized dermatological training, to make more confident and timely referral decisions, ensuring high-risk patients see a specialist sooner.

Prostate Cancer: The Gap Between the Lab and the Clinic

The case of prostate cancer detection using multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) offers a crucial, sobering lesson about the challenges of real-world implementation. While mpMRI is the diagnostic standard, its interpretation can vary significantly between radiologists.

- In Research Settings: AI has shown exceptional promise. The large-scale PI-CAI study found that an AI system outperformed general radiologists on average, achieving a superior Area Under the Curve (AUC), a key measure of diagnostic ability, of 0.91 compared to the radiologists’ 0.86.

- The Reality Check: However, when these promising algorithms are moved from the clean, curated datasets of a research study into the messy, variable environment of a live hospital workflow, their performance can degrade dramatically. A narrative review of real-world AI implementations for prostate MRI found an average performance drop of 12%. In one stark example, a major cancer center had to terminate its deployment after the AI’s specificity dropped by an unacceptable 31%.

The contrast between the successful large-scale implementation in the PRAIM breast cancer study and the struggles in prostate cancer highlights the critical “last mile” problem. An algorithm’s technical accuracy is only one part of the equation. Success depends equally on seamless integration with existing hospital IT systems (like PACS), managing issues like “alert fatigue” among clinicians, and building trust with the radiologists who use the tool. This “translation gap” between research and clinical practice is one of the biggest hurdles the field must overcome.

The Fuel for the Revolution: The Power of Big Data

AI algorithms are not born intelligent; they are made intelligent through training. The essential fuel for this process is data, high volume, high-quality, and diverse datasets.The performance of any AI model is fundamentally limited by the quality and quantity of the data it learns from; studies have shown that model accuracy improves as the size of the training dataset increases.

Recognizing this critical need, the scientific community has established major public initiatives to collect and share medical data for research. A leading example is The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA).

- Funded by the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI), TCIA is a large, publicly available archive that hosts de-identified medical images of cancer.

- It contains vast collections of CT scans, MRIs, and digital pathology slides from thousands of patients.

- Crucially, these images are often linked to vital supporting data, such as patient outcomes, treatment details, and genomic analyses.

Initiatives like TCIA are the bedrock of AI development in oncology. They provide researchers and engineers around the world with the raw material needed to build, train, and validate new algorithms, accelerating the pace of innovation and enabling the breakthroughs discussed in this article.

However, the reliance on data also introduces one of the field’s most significant challenges: the “garbage in, garbage out” principle. The quality and diversity of training data are paramount. If an algorithm is trained only on images from one hospital’s scanners or from patients of a single demographic group, its performance may plummet when used in a different setting or on a different population.

This risk of bias is a major concern. An algorithm that is not trained on a sufficiently diverse dataset could perpetuate or even amplify existing health disparities, for example by being less accurate for certain ethnic groups. Ensuring that training datasets are equitable and representative of the global population is a critical challenge for the entire field.

A Cautious Optimism: Navigating the Challenges Ahead

For AI to be safely and effectively integrated into routine cancer care, the medical and technology communities must navigate a series of significant technical, ethical, and logistical hurdles. The path forward requires a cautious optimism, balancing excitement for the technology’s potential with a clear-eyed view of its limitations.

- The “Black Box” Problem: Many advanced deep learning models are considered “black boxes.” They can make astonishingly accurate predictions, but it is often impossible to know exactly why they arrived at a specific conclusion. This lack of transparency, or “explainability,” is a major barrier to clinical adoption. Doctors are understandably hesitant to trust and act upon a recommendation from a system whose reasoning they cannot understand. This challenge is so fundamental that it has spawned a new sub-field of research known as Explainable AI (XAI), which focuses on developing techniques to make AI models more transparent and interpretable.

- Data Privacy and Security: The development of AI requires access to vast amounts of sensitive patient health information. Protecting this data from breaches and ensuring patient privacy is a paramount ethical and legal obligation.

- Algorithmic Bias: As previously discussed, if training data is not representative, the resulting AI can be biased. This poses a serious risk of creating a two-tiered system of care where AI tools work better for some populations than for others, worsening health inequities.

- Accountability and Liability: A critical unanswered question looms over the field: who is responsible when an AI system makes a mistake that leads to patient harm? Is it the doctor who followed the AI’s suggestion, the hospital that purchased the software, or the company that developed the algorithm? Currently, there are no well-defined legal or regulatory frameworks to address this complex issue of liability.

Conclusion: The Future of Cancer Detection is a Human-AI Partnership

The evidence is clear: Artificial Intelligence is a transformative force in oncology. It is not a single cure for cancer, but it is accelerating nearly every step that leads us closer to controlling and managing it more effectively. By harnessing the power of deep learning, AI algorithms are demonstrating a remarkable ability to detect cancer earlier and more accurately across a range of malignancies, as proven in large-scale clinical studies.

The journey ahead is not without its challenges. The ethical questions of bias and accountability, the technical hurdles of clinical integration, and the fundamental need for transparency must be addressed with rigor and care. Yet, these are not insurmountable barriers but rather the defining tasks for the next phase of medical innovation.

The ultimate vision is not one of machines replacing doctors, but of a powerful and symbiotic partnership. In this future, AI will handle the immense task of data analysis, sifting through millions of images and records to find the subtle signatures of early disease. This will empower clinicians, freeing them to do what they do best: apply wisdom, context, and empathy to make the best possible decisions for their patients. By combining the tireless precision of the machine with the expert judgment of the human, we are moving toward a future where a cancer diagnosis is less often a feared verdict and more often a manageable condition, caught at its earliest and most treatable stage

1. How exactly does the partnership between AI and cancer detection work in a clinical setting?

AI acts as a powerful assistive tool, not a replacement for doctors. In medical imaging, for example, an AI algorithm can pre-screen thousands of mammograms or CT scans, flagging the most suspicious cases for a radiologist’s review. This creates a symbiotic partnership where the AI handles the data-intensive initial analysis, allowing the human expert to focus their cognitive energy on complex diagnoses and patient care.

2. Can AI and cancer diagnostics really outperform human radiologists?

In controlled studies, AI has shown the potential to match or even exceed human performance on specific tasks, such as finding more cancers in mammograms. However, the real-world goal of AI and cancer care is not a competition but collaboration. AI excels at rapid, consistent pattern recognition, which augments a radiologist’s expertise, leading to a more efficient and accurate overall diagnostic process.

3. What are the biggest challenges in integrating AI and cancer care more widely?

Key challenges include the “black box” problem, where it’s difficult to understand how an AI reached a conclusion, and the risk of algorithmic bias. If an AI is trained on non-diverse data, its performance may be less accurate for underrepresented populations. Ensuring transparency, equity, and seamless integration into existing hospital workflows are critical hurdles that must be overcome.